- Home

- Peter Shapiro

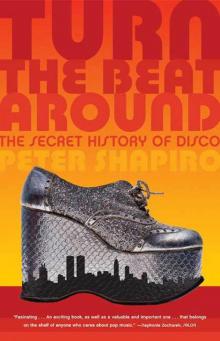

Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco

Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Rachael

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to everyone involved in this project, whether by providing inspiration, granting interviews, helping me chase down leads, or feeding my vinyl jones: Nile Rodgers, Sooze Plunkett-Green, Bob George, Danny Wang, Danny Krivit, Michael “Lucky Strike” Corral, Tom Moulton, Ian Levine, Daniele Baldelli, Cherry Vanilla, Vicki Wickham, Barry Lederer, Bob Blank, Quinton Scott, Toni Rosano, Drew Daniels, Martin Schmidt, Dan Selzer, Chris at Dfiledamerica, Jeff Chang, David Toop, Sasha Frere-Jones, Mike Rubin, Dave Tompkins, Philip Sherburne, Rob Michaels, $mall ¢hange, Jonathan Buckley, and Mark Ellingham. Sections of this book have appeared in different form in The Wire, and I’d like to thank my editors there (Tony Herrington, Rob Young, and Chris Bohn) for allowing my theoretical ramblings on disco to appear in such an august journal.

Thanks to my agent, David Smith, and my editors, Denise Oswald and Lee Brackstone. Extra special thanks to my wife, Rachael, for putting up with my ridiculously late nights and the creeping monster that is my record collection; for cracking the whip; and for giving me never-ending amounts of support.

1

THE ROTTEN APPLE

A dance is the devil’s procession, and he that entereth into a dance, entereth into his possession.

—St. Francis de Sales

Hello from the gutters of N.Y.C. which are filled with dog manure, vomit, stale wine, urine and blood.

—David Berkowitz

Fee fie fo fum

We’re looking down the barrel of the devil’s gun

Nowhere to run

We’ve got to make a stand against the devil’s gun.

—CJ & Co.

To many, disco is all about those three little words: “Halston, Gucci, Fiorucci.” Others undoubtedly have images of long-legged Scandinavian ice queens in metallic makeup and dresses “cut down to there” dancing in their heads. Or maybe it’s the tête-à-tête between Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger in the VIP room of Studio 54, each trying to outdo the other with their looks of supercilious boredom. Disco is all shiny, glittery surfaces; high heels and luscious lipstick; jam-packed jeans and cut pecs; lush, soaring, swooping strings and Latin razzmatazz; cocaine rush and quaalude wobble. It was the humble peon suddenly beamed up to the cosmic firmament by virtue of his threads and dance moves. Disco was the height of glamour and decadence and indulgence. But while disco may have sparkled with diamond brilliance, it stank of something far worse. Despite its veneer of elegance and sophistication, disco was born, maggot-like, from the rotten remains of the Big Apple.

In the early 1970s, the words “New York City” became a shorthand code for everything that was wrong with America. Movies like Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, Taxi Driver, The Panic in Needle Park, The Prisoner of Second Avenue, The Out-of-Towners, Dog Day Afternoon, Shaft, Across 110th Street, and Death Wish depicted a city on the brink: a cesspool of moral and spiritual degradation; a playground for drug dealers, pimps, and corrupt cops; the government an ineffectual, effete elite running its fiefdom from cocktail parties in high-rise apartments seemingly miles above the sullied streets; the only recourse for the ordinary citizen to grab a gun and start shooting back. As New York Times film critic Vincent Canby wrote, “New York City has become a metaphor for what looks like the last days of American civilization. It’s run by fools. Its citizens are at the mercy of its criminals who, often as not, are protected by an unholy alliance of civil libertarians and crooked cops. The air is foul. The traffic is impossible. Services are diminishing and the morale is such that ordering a cup of coffee in a diner can turn into a request for a fat lip.”1

Only a few years earlier, in 1967’s Barefoot in the Park, the city was the setting for young love and newlywed highjinks. Sure, the Bratters’ Greenwich Village apartment was small and cramped, but the conspicuously beautiful and well-scrubbed Robert Redford and Jane Fonda could scamper about Washington Square Park without shoes and have picnics if they needed to escape. By 1971, the newlyweds would’ve been played by Ernest Borgnine and Karen Black, and walking barefoot in any of the city’s parks would have got them one-way tickets to Mount Sinai for a tetanus shot. How did things change so quickly?

To fully comprehend New York in the seventies, it’s necessary to look at where the previous decade and its progressive agenda fell off course. The liberal experiment of the 1960s was fueled by the youthful enthusiasm and swaggering confidence of a generation that had never known anything but the greatest prosperity the world had ever seen. But as soon as the economic conditions that had made the Great Society possible started to falter, the dreams turned into disillusionment, the promises became retractions, and the sweeping vision became blinkered and myopic. The civil rights marches devolved into “race riots,” “flower power” wilted and turned into “the year of the barricades,”2 and “groovy,” “peace,” and “love” were traded for “Up against the wall, motherfucker.”3 Two of the figureheads of the Old Left, Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, were assassinated in the spring of 1968, and a few weeks later the full force of the Chicago Police Department was unleashed on protesters outside of the Democratic National Convention. Vietnam, numerous ecological disasters, and oppressive mores turned young people against the scoundrels running the government and big business, and against the Establishment in general; meanwhile, the previous generation was bemoaning the lack of respect for authority and the loss of “values.” In response, both the Left and Right became increasingly militant and increasingly intractable in their positions. Gone were the beloved communities of the civil rights marchers, protest singers, antiwar activists, and Woodstock nation, and their spirit of inclusion, participation, and democracy in action. Instead, the onset of the 1970s brought identity politics, special-interest groups, EST retreats, armed street gangs, “corporate rock,” tax revolts, and a politics of resentment, and attendant with all of this feelings of alienation, resignation, defensiveness, frustration, and betrayal. A kind of siege mentality replaced the “great consensus” that had previously characterized American life.

Although Harlem and the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant erupted into riot on July 18, 1964, when a police officer who had shot and killed a black teenage boy two days earlier was exonerated, New York’s 1960s “race riot” was relatively small (one dead and one hundred injured) compared to the riots that ravaged other American cities like Detroit, Los Angeles, and Newark. Nevertheless, the scars were just as deep. As with these other cities, New York had experienced enormous demographic changes since the 1930s. Northern cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia were the goal for millions of poor rural African Americans who migrated northward during the 1930s and ’40s.4 In 1965, the immigration quota laws that effectively prevented anyone who wasn’t from Western Europe from entering the country were relaxed, allowing huge num

bers of Asians, Latin Americans, and Afro-Caribbeans to enter the United States—so much so, that by the mid-1980s, there were more first-generation blacks from the West Indies in New York City than African Americans who were born in the United States.5 Unfortunately for New York, the vast majority of these newcomers were unskilled workers, and they arrived at exactly the time the manufacturing industries that had formerly provided them with jobs started to decline—a downturn that was exacerbated by a recession that began in the late 1960s and would hit New York harder than any other metropolitan area.6 To further compound the problem, this influx of immigrants was concurrent with a massive exodus of the city’s white population to the suburbs.7 White flight coupled with the recession meant that the city’s tax revenues shrunk drastically—at exactly the same time that the municipal government was forced to dramatically increase its budget.8

While the ranks of the city’s bureaucracy necessarily swelled, services were cut proportionally in order to pay for the expansion of the municipal government. The city stopped investing in infrastructure and could barely pay its most important employees. Sanitation workers staged strikes during summer heat waves, turning the Big Apple into a festering trash heap tended by the city’s twenty-five million rats. To save on overtime payments, firefighters “were dispatched to blazes in dial-a-cabs to relieve those ending their shifts.”9 Cynical, underpaid policemen fought a losing battle with crime: Between 1966 and 1973, New York’s murder rate jumped a staggering 173 percent and rapes 112 percent.10 The Knapp Commission Report, issued in December 1972, said that police corruption “was an extensive, department-wide phenomenon that included cops selling heroin, ratting on informants to the mob, and riding shotgun on drug deals.”11 A new priority for police officers was the result: “Stay out of trouble and avoid the appearance of corruption.”12 “[A] proactive police department that kept order on the streets by showing a strong street presence” suddenly became “a reactive department that patrolled neighborhoods by car instead of foot.”13 The subways were ceded to the muggers and thugs; and if you weren’t physically assaulted, you were visually besieged by the graffiti writers’ brutal and aggressive tags and burners. The one area where police resources were significantly expanded was in the battle against the drug epidemic: Drug offenses that had been previously punishable by probation and a stay at a residential drug treatment program now carried with them mandatory minimum prison terms.14

The result was a creeping blue funk that swept over the city, instilling everything with a sense of dread and foreboding. As The New York Times’s David Burnham wrote, “The fear is visible: It can be seen in clusters of stores that close early because the streets are sinister and customers no longer stroll after supper for newspapers and pints of ice cream. It can be seen in the faces of women opening elevator doors, in the hurried step of the man walking home late at night from the subway. The fear manifests itself in elaborate gates and locks, in the growing number of keyrings, in the formation of tenants’ squads to patrol corridors, in shop buzzers pressed to admit only recognizable customers. And finally it becomes habit.”15

Meanwhile, landlords began a concerted, if largely unorganized, campaign of disinvestment in an effort to overturn the city’s rent control regulations and to squeeze every inch of profit they could out of their properties. As “desirable” tenants fled to the suburbs, rather than accept controlled rents from the city for low-income tenants, landlords neglected their maintenance responsibilities, stopped providing utilities, refused to pay taxes, and eventually indulged in arson on their own properties, leaving vast areas pockmarked with burned-out buildings, destroying communities and neighborhoods in the process.16 The worst ravaged area was the South Bronx (the communities of Mott Haven, Morrisania, and Hunts Point), a few square miles just over the Willis Avenue Bridge from Manhattan that had been abandoned to the drug abusers, street gangs, and roving packs of wild dogs, and largely left for dead. Dr. Harold Wise of the neighborhood’s Martin Luther King Jr. Health Center called the place “a necropolis.”17

In the late ’60s, organizations like the Black Panther Party and Nation of Islam attempted to act as the sheriffs in these urban ghost towns, but their influence was waning in the face of the FBI’s COINTELPRO (a massive covert action program that sought to “neutralize” what FBI director J. Edgar Hoover called “Black Nationalist hate groups” and “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”).18 The void left in their wake was filled by street gangs like the Black Spades, Savage Skulls, Roman Kings, Javelins, and Seven Crowns to which disenfranchised young African-American and Hispanic men turned in droves.19 By 1973, there were 315 gangs with more than 19,000 members in New York City.20 Even though many of these gangs evolved into politicized empowerment groups like the Young Lords Party and the Real Great Society (which grew out of the Lower East Side Dragons and the Assassins) and started to attack the drug dealers who ravaged their neighborhoods with heroin, the gangs’ association with violence and their intimidating presence colored the city with a steely brutality. As Nelson George noted, “Civil rights, self-sufficiency, protest, politics … all of it faded for those trapped in the shooting galleries of the body and the mind.”21

New York’s members of the Silent Majority who had swept Richard Nixon into power in 1968 felt like they were being outnumbered and ignored, and reacted with fear and resentment. Their response to growing black militancy, the antiwar movement, bra burning, major demographic change, and hedonistic hippies “tuning in, turning on, and dropping out” was America’s thermidorean reaction and prompted Time magazine to name the Middle American as its Man and Woman of the Year in 1969.22 The Middle American was the square heartlander who rallied around Old Glory and still believed in Mom, baseball, and apple pie; he was the anti-intellectual narrator of Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” who doesn’t “smoke marijuana … take trips on LSD [or] burn [his] draft card down on Main Street [because he likes] livin’ right and being free”; she was the mother concerned about kin and decency who put an “Honor America” bumper sticker on the family car. These Middle Americans were the ones responsible for a law in West Virginia that absolved the guilt of any policeman involved in future deaths of antiwar protesters or race rioters, the ones who defied almost two hundred years of separation between church and state to encourage their kids to pray in a public school in Netcong, New Jersey.

Despite being that den of iniquity and vice so close to decadent Europe and the seat of the Northeastern liberal elite, New York City had its own Middle Americans—the working-class white ethnics who lived in the outer boroughs. They were, as described by New York City mayor John Lindsay’s biographer Vincent J. Cannato, “men and women descended from German, Irish, Italian, Polish, Greek and Jewish immigrants who were either civil servants (teachers, firemen, policemen), union members (welders, electricians, carpenters), or members of the petite bourgeoisie (clerks, accountants, small businessmen). Their culture was middlebrow, traditional and patriotic.”23 They were enshrined in popular culture by All in the Family’s Archie Bunker, who became the country’s favorite TV character as soon as he appeared in 1970. His vision of America was “the land of the free where Lady Liberty holds her torch sayin’ send me your poor, your deadbeats, your filthy … so they come from all over the world pourin’ in like ants … all of them free to live together in peace and harmony in their separate little sections where they feel safe, and break your head if you go in there. That there is what makes America great!”24

The Bunkers were traditional Democratic voters who had grown disenchanted with the liberal experiment of the 1960s and blamed it for tearing apart the fabric of American society. One particular target of their ire was the welfare program, which in the popular imagination had become permanently associated with African Americans and had exploded out of control.25 But since welfare did nothing to address the real problems of ghetto life, racism, and endemic poverty, urban African Americans continued to protest vociferously their social an

d economic conditions. “But,” as writer Peter Carroll noted, “these complaints seemed particularly outrageous to working-class whites, who themselves teetered on the brink of economic disaster.”26 In a chilling article in New York magazine, veteran New York newspaperman Pete Hamill wrote that the white working and lower middle classes “see a terrible unfairness in their lives and an increasing lack of personal control over what happens to them.” Instead of turning to the government or the unions or community groups for help, they were increasingly arming themselves, forming vigilante groups, and talking of a race war. Hamill ominously warned that “All over New York City tonight, in places like Inwood, South Brooklyn, Corona, East Flatbush and Bay Ridge, men are standing around saloons talking darkly about possible remedies. Their grievances are real and deep, their remedies could blow this city apart.”27

Even though the prophesied race war never happened, on May 8, 1970, their grievances bubbled over into physical violence. A group of about two hundred construction workers carrying crowbars and hammers descended on a gathering near City Hall of one thousand students who were protesting the deaths four days earlier of four students who were killed by members of the National Guard at an antiwar protest at Kent State University in Ohio. Chanting “All the way, USA,” they beat the protesters with their helmets, tools, and steel-toed work boots to the accompaniment of applause from the suited and tied executives at the brokerage houses overlooking the square. “Bloody Friday” was only the beginning of two weeks of virulent flag-waving, pro-Nixon demonstrations that were known as the “Hard Hat Riots” and culminated on May 20, when between 60,000 and 150,000 construction workers and their allies marched down the Canyon of Heroes in lower Manhattan in a tickertape parade.28

Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco

Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco